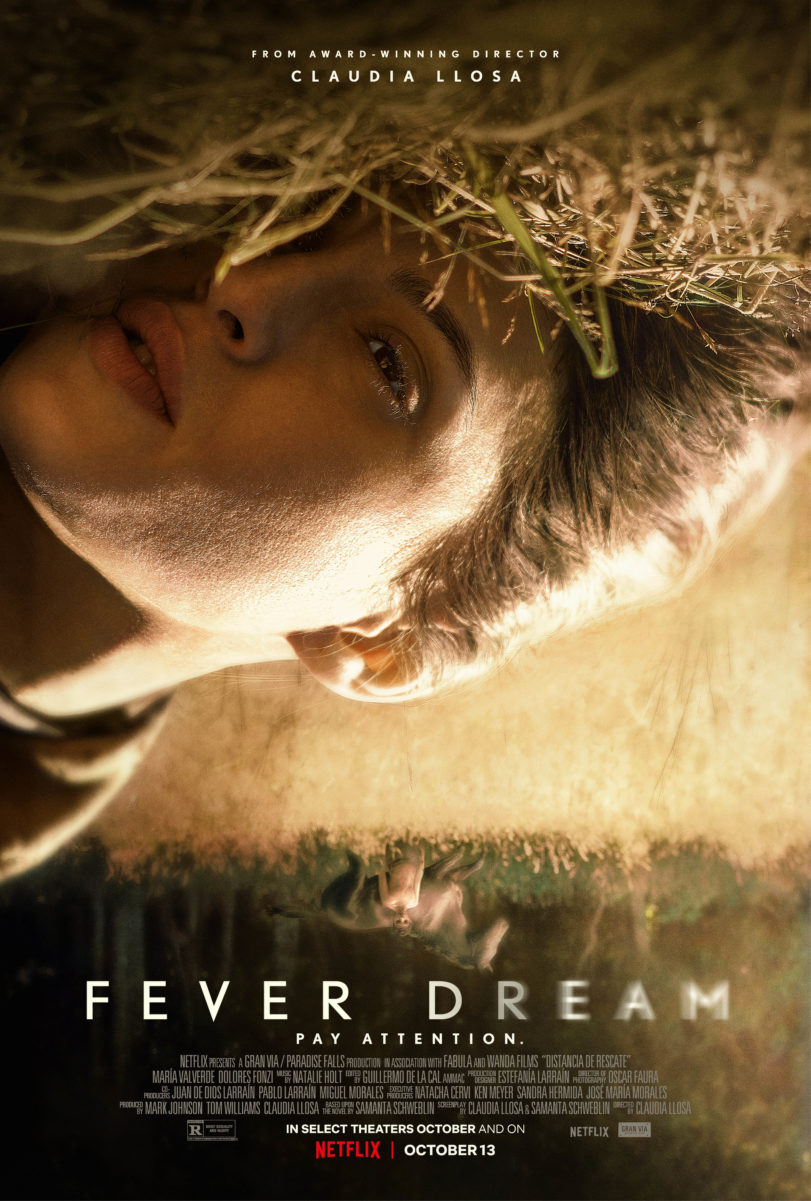

For the audience, Fever Dream unfolds like a spiritual metamorphosis. Shrouded in mystery and tension, the movie is a psychological trip into the meaning of maternal love.

Baked on the book by Samanta Schweblin, Fever Dream tells the story of the relationship between two young mothers — one a visitor, the other, a local, and reveals the forms that nature and horror can intertwine.

We had the chance to interview the director Claudia Llosa and the author of the book, Samanta Schweblin. Both worked together to create the film’s screenplay.

Fever Dream premieres today on Netflix.

The first question is for Samantha. Tell me a bit about the writing process with Claudia. What was it like revisiting Fever Dream?

S: Ah well, it was quite an adventure. The truth is that at first I entered with a bit of resentment because I wondered if as the author of the novel, I would have enough distance to rethink this whole story from the language of cinema. I didn’t really know what was going to happen to me with that, if I was going to be able to really let go. It seems to me that in an adaptation, the first thing you have to do is give up the material you are going to work with and I didn’t know if I was going to be able to do it or not. But after the truth is that the work with Claudia worked, I would not say well, I would say spectacular! I felt very safe, very, very calm, very accompanied. I felt that there was a moment in writing in which the limits between what she did and what I did were blurred, that each one really put in a lot of generosity. In other words, I felt in such a space, I felt so comfortable, there was so much confidence that I was not afraid to let go, let go, let go, let go. And there was times when we were literally running through or re-running through this whole story all over again. But with materials as different as those of the cinema, in comparison with those of the fiction, that the enjoyment was once again genuine. I do not know how. In other words, I had reconnected with the story again from a completely different place and that made the interest and the route and the distance new as well.

Claudia, after reading the book, what topics were you most interested in exploring in the movie?

C: Well, the themes have always interested me. The themes that the novel dealt with have crossed me before, that is, the fear of motherhood, the complexity of the feminine and magical thinking, this idea of how we move in different interpretations. But there was something that seemed spectacular to me, which is physically putting a name to something that I had felt so many times as a mother, as a daughter, which was precisely that distance to rescue. A sensation so physical, so tangible and at the same time so spectacular to explore in a movie, right? That fear? To precisely not arrive on time, to lose, right? To lose the possibility of taking care of your child, of saving them, of protecting them. But on the other hand, also giving them the freedom for him to express themselves, for them to travel, for them to move, for them to make mistakes. And how? How do we work, how do we accommodate that place? As mothers, it seemed like a very pertinent question to me. More so at a time so linked to control and the obsession about control and another element that seemed extremely rich and extremely attractive to me was the idea of entering the world of osenos, but not from a classic version, but from this conversation, from these two fascinating characters. This boy who seems to understand what we do not understand, what we do not see and who begins to order Amanda’s story be told because needs to understand. That he has that urgency, that urgency charged with the denouncement that the story ultimately has. And those elements were just awesome, very important to me.

Samantha the book is your baby. Was there a scene or sequence that you found difficult to translate to the screen?

S: Well, there is a great scene that runs through the whole novel from start to end and it is very abstract in the novel, which is that space in which Amanda and David talk, right? That for me, it is a very abstract space and it worked very well as an abstract space in the novel because it was a space that I played with precisely this idea. Because the space wasn’t really where this is really happening, it’s in Amanda’s head, it’s in the reader’s head. But that abstraction that worked in literature and in cinema it could not work if it did not materialize in something in particular. That was perhaps the most difficult move. But Claudia, in the first meeting we had, she had already come up with an adaptation idea for that, which also seemed brutal to me. It seemed so wise. I think one of the reasons why I loved the idea of working with Claudia was because of this particular idea, because of the way she communicated it to me, the details she told me made me understand up to what point were we reading the book on the same emotional level, tension level, communication level with the viewer. So yeah, we would talk about that place.

Claudia, there was a really beautiful use of sound and nature throughout the film, especially near the end, when there is the big reveal of the film. Can you talk a little more about how you found and created that perfect balance between all the elements?

C: Well, I have to say that it was a very long process, because I think it is the first film in which the sound element appeared to me. The voices in the off had to have to have a clear physical place which forced me to think about the sound from a totally new place. And I needed to give that place a space that can evoke and appear and disappear in some moments, from the very nature of the environment to something much more abstract, even terrifying. And it was a combination, obviously, the work of Fabiola Ordóñez, the sound designer, the work of Jamie Oliver, who is a Peruvian musician friend who teaches in Wayuu, who is a spectacular creator. They are very new sound elements. Obviously what ended up really exploding for me was having Natalie Wood with us, who is extraordinary and who has a sensitivity and what most precisely cost us.at the same time she found it was that tempo. That final piece that she had, because we knew that we had to end in this very powerful way. But that piece could not come out of nowhere, the beginning had to be constructed in a very subtle way. So we couldn’t begin to compose the beginning until we had that ending. And she on a return trip, I think, from Barcelona to London, listened to it. She started composing it on and it pinned my body and somehow I felt that was it, right? And from there we started to build everything, let’s say, the whole game of those three elements that come together until they explode in the final composition that there is, which is really very special.

My final question is for Samantha, what do you hope fans of the book like about the movie?

My final question is for Samantha, what do you hope fans of the book like about the movie?

S: Ah, I think the same thing that I hoped about the book because in the end, they are connected. In that sense, it seems to me that both the book and the movie work as a strong denouncement. There is an urgency from the order of political denunciation, which almost asks you to stop watching or to stop reading and run away, or try to google the subject and try to understand what is happening and to what extent that could touch you. That is why the urgency, the tension and all of this happening to the viewer in their body was so important to me. That feeling of I can’t take it anymore. When I was writing this novel I was thinking, but will it be? It was about connecting with myself, as a reader, right? What I realized while trying to analyze myself as an overdraft, as a reader, I thought well, in general sometimes I forget the numbers, the statistics, the names in fiction, but I will never forget the fear when they make me feel it in my body. That for me is something that leaves a mark, right? So what did you want? I wanted that in the readers and hopefully there is some of this in the viewers as well.